Welcome back to Thebeerchaser. If you are seeing this post through an e-mail, please visit the blog by clicking on the title above to see all of the photos at the end of the post and so the narrative isn’t clipped or shortened. (External photo attribution at the end of the post #1)

The distance between the Port of Sydney on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia and Halifax, the destination on the sixth day of our Holland America cruise from Montreal to Boston was 277 nautical miles.

This meant the MS Volendam sailed most of the late afternoon and the night in the Atlantic Ocean allowing us to arrive the next morning in Halifax. (#2)

While the Volendam was refreshingly smaller than the two prior Holland America ships on which we cruised, it’s still a very large vessel. Its maiden voyage was in 1999. Maximum speed is 23 knots.

With a total of ten decks, it has capacity of 1,432 passengers and complement of 647crew members. We could work off the excellent food by walking around the third deck – 3.5 rounds made a mile.

Gross Tonnage *1 60,906

Length 778 feet – 237 meters

Beam *2 106 feet – 32.3 meters

*1. Gross Tonnage is not a reference to the weight of a cargo ship. It refers to the capacity of a ship’s cargo. Tonnage is more of a metric for the government to levy taxes, fees, etc. The displacement tonnage of a ship (see below) is the ship’s weight.

*2. The beam is the width at the widest point.

The weather was better which meant some time to view the scenery as well as the nautical traffic. The latter fascinates me and brought back some memories of the two ships I was on during my brief service in the Navy which I’ll mention below.

For example, we passed the freighter – Algoscotia (shown below) – launched in 2004 and one of seven vessels owned by Algoma Tankers Ltd. – a subsidiary of Canada’s largest inland shipping company.

The ship is a chemical/oil tanker and according to one vessel-finder website, was sailing to Portugal. It’s currently docked in New York Habor.

Maritime Sidenote – I had a recent conversation with my former Schwabe law firm Managing Partner, Dave Bartz – not only an outstanding environmental lawyer, but also an expert in admiralty law.

I mentioned the cargo ship, MV Dali collision with the Francis Scott Key Bridge in March. Dave, in his continuing efforts to educate me, pointed out that it was actually an “allision.”

“In a collision, two moving objects strike each other; for example, two passing ships. An allision, however, involves an accident where only one of the objects is moving.

For instance, this maritime term can refer to an accident where a moving boat runs into a stationary bridge fender.” (Arnold and Itkin law firm)

(I subsequently used that fact in numerous conversations trying to show my erudition and now you know too.) (#3 – #4)

For comparison purposes and to better understand the damage caused to the bridge, the Dali is a larger vessel than the Volendam with a gross tonnage of 95,000 vs. 61,000, a length of 984 feet vs. 778 feet and a beam of 158 feet vs.106 feet.

Digression — A Bit of Maritime Nerdery

Seeing the Algoscotia piqued my interest in light some of the similar freighters we saw on our 2017 Panama Canal cruise and the infamous Ever Given – involved in the 2021 Suez Canal obstruction.

It also harkened back memories of the USS John R. Craig – DD885 and the USS Bradley DE1041 – in the Navy destroyer and destroyer escort I spent some time on during NROTC midshipman summer training cruises in college.

For example, take a look at the statistics for the Algoscotia:

Gross Tonnage: 13,352

Length: 489 feet -149 meters

Beam: 24 meters

Now, the freighter is a big ship up close, but the Volendam dwarfed her – 1.6 times longer and a heck of a lot more volume or carrying capacity – close to five times – 61 tons compared to just over 13.

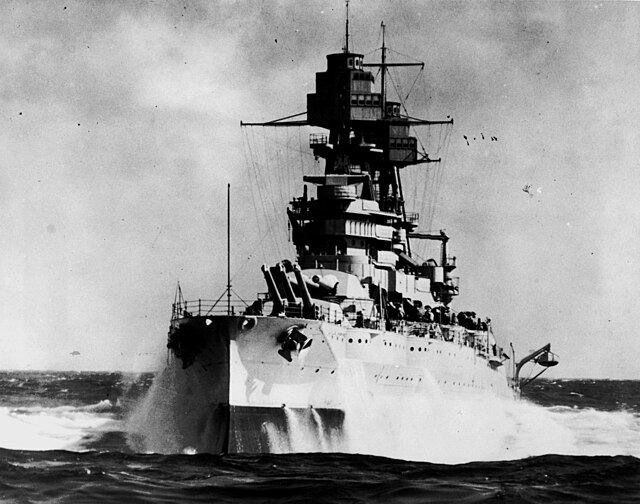

The USS John R. Craig

The John R. Craig, commissioned in 1945, was an old destroyer when I spent the summer of 1967 as a 3/c midshipman – a lot of it in the engine room and boiler room. Maximum speed was 34 knots.

This great ship had its ultimate demise twelve years later when it was decommissioned on 27 July 1979 and then sunk as a target off California on 6 June 1980. (#5)

USS John R. Craig – DD885

The John R. Craig had a total complement of 336 officers and crew. Now as a naive college NROTC guy, I thought it was a pretty big ship – over the length of a football field at 390 feet long – but you can see from the structural data below the Volendam was almost twice as long.

Displacement 3,460 tons

Length 390 feet – 119 meter

Beam 41 feet – 12.5 meters

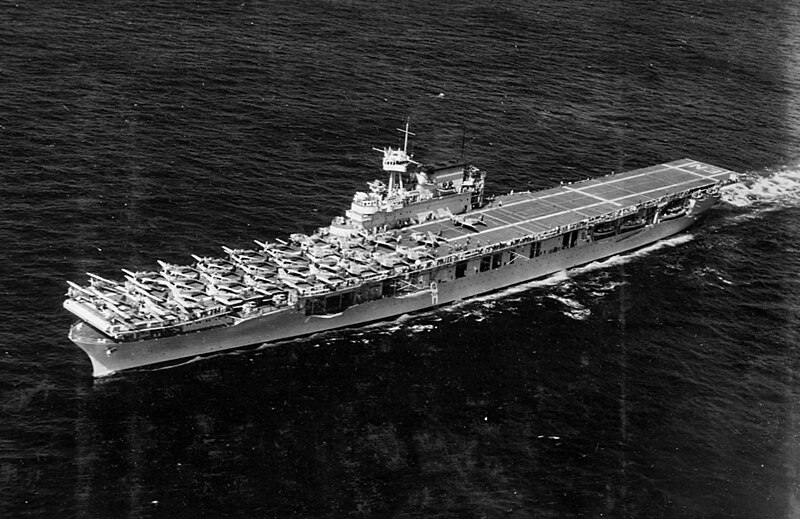

The USS Bradley (#6)

USS Bradley – DE1041

I spent over three months on the Bradley, the summer of 1970, on a 1/c midshipman cruise. I was fortunate because I was the only 1/c midshipman on that vessel and the Executive Officer told me that I would replace the lieutenant in charge of the Deck Division when he went on leave in two weeks until he returned.

The Bradley was a much newer ship – launched in 1965, twenty years after the John R. Craig – with a total complement of 247 of which sixteen were officers. Maximum speed was 27 knots.

The Bradley had a less ignominious ending than the Craig. In September 1989, she was leased to Brazil and became the destroyer Pernambuco (D 30). She remained active in the Brazilian Navy into her 39th year afloat. The eventual auction and dismantling by a private company is fascinating.

Displacement 2,624 tons

Length 414 feet – 126 meters

Beam 44 feet – 13.4 meters

I became friends with the officers on the Bradley – it had a squared-away crew and commendable morale. I extended my time on the cruise until the officer returned from leave because of this.

The Captain had requested that I return to the ship upon my commissioning in March,1971 and I had orders to the Bradley. Unfortunately, skull injuries from a serious auto accident in January,1971 essentially ended my Navy service before that occurred.

How Big is Too Big??

Now, I was amazed at the size of the Liberian container ship MSC Arushi when she passed us in the Panama Canal in 2017. Her gross tonnage is 44,803 tons and length overall 921 feet (more than three football fields) with a container capacity of 4112.

The Suez Canal obstruction by the cargo ship Ever Given in 2021 raises the question as to whether there should there be limits to the size of vessels for a number of practical reasons.

“…. the Suez Canal was blocked for six days by the Ever Given, a container ship that had run aground in the canal. The 400-metre-long (1,300 ft), 224,000-ton, vessel was buffeted by strong winds on the morning of 23 March and ended up wedged across the waterway with its bow and stern stuck on opposite canal banks, blocking all traffic until it could be freed.” (Wikipedia) (#7 – #8)

The Arushi, mentioned above, looked massive, but compared to the Ever Given almost seems like a yacht. The Ever Given – one of the largest ships ever built – is more than the length of four football fields and 400 feet longer than the Arushi. She can hold five times as many containers, or 20,124.

Keep in mind these facts for a standard 20-foot container:

“The standard dimensions are 20 feet long and eight feet wide. They weigh 5,200 pounds when empty and 62,000 pounds when fully loaded. The internal volume is the equivalent of 200 standard mattresses, two compact cars, or 9,600 wine bottles.” (Boxhub.com). (#9 – #10)

Whoa Baby!

Okay hypothetically, let’s say that you’re the Officer of the Deck of a large cargo ship and your radar operator reports a large “skunk” – (the common label used for unknown surface radar contacts – readyayeready.com) dead ahead on the horizon.

Now bear with me, so to speak, because the scenario may not be very probable, but it will help demonstrate my point below. You want to be cautious, so you order the helmsman who relays it to the ship engineer, “All engines stop – rudder amidship.”

How long does it take the vessel to stop? (#11)

Who are those guys anyway??

The answer is “More time (and distance) thank you think.”

“The stopping distance for a cargo ship depends on factors such as displacement, trim, speed, and type of machinery. Most vessels will travel approximately 5 to 12 times their own length before coming to rest from full ahead, taking 4 to 10 minutes to do so.

Large ships may require up to 5 miles to stop when in full reverse. (emphasis supplied – (https://knowledgeofsea.com/emergency-stop-manoeuvre/).

Rethinking Configurations

You have to pardon me for this long detour on maritime stuff and will have to wait for the next post to hear about Halifax and a great brewery there, but I couldn’t help myself although real naval experts can probably eviscerate some of my assumptions and statistics.

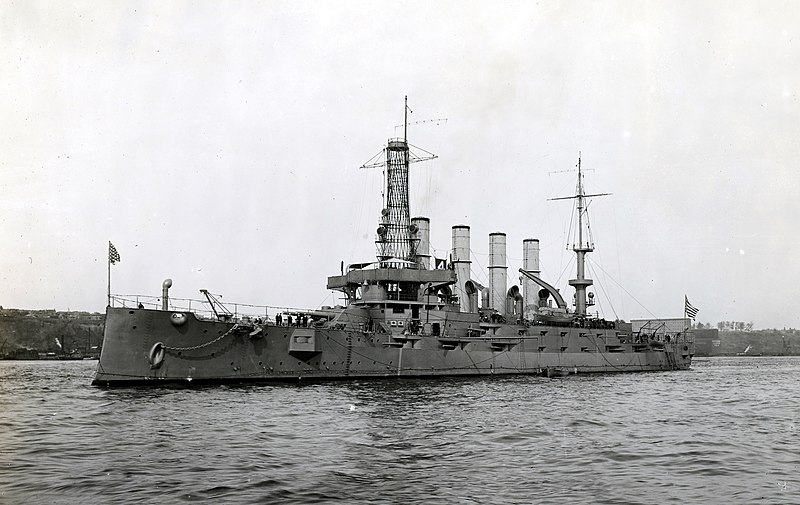

During World War II and to a certain extent to the current time, the large Navy ships such as aircraft carriers, battleships and cruisers have been the mainline weapons of the Navy along with submarines.

Take a look at these older vintage Navy ships. (Clockwise left to right: the battleship USS Arizona (BB39), the aircraft carrier USS Enterprise (CV6), the cruiser USS North Carolina (ACR12) and the Destroyer USS Wallace (DD703) (#12 – #15)

Compare these with the modern versions of battleships, aircraft carriers and cruisers. Even destroyers, known for the agility and maneuverability are a far cry from the USS John R. Craig as can be seen by the photo of the Zumwalt Class Destroyer.

Clockwise from left: Guided Missile Cruiser USS Philippine Sea (CG58), Aircraft Carrier USS Gerald R Ford (CVN78), Littoral Combat Ship USS Tulsa (LCS16) and Guided Missile Destroyer USS Zumwalt (DDG1000) (#16 – #19)

The Future

Navy admirals will always push for more ships with more firepower – usually larger and more expensive. But is that the best overall strategy?

Alfred Thayer Mahan (1840 – 1914) – naval officer and historian and author of one of the most significant and influential naval books in history, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660–1783 might turn over in his grave if he read the following article:

Big U.S. Navy Warships: Did Drones and Missiles Just Make Them Obsolete?

“The warship is not categorically out of date, and the world’s most important militaries are still investing heavily in warships. But current trends suggest the large warship will become increasingly contested, and perhaps less effective as a result…

Deploying an anti-ship missile (or drone) is a relatively cheap way to counter a warship that can cost billions of dollars and can carry several thousand sailors. Missiles have the potential to create parity between disparately situated nations… (#20 – #21)

At the moment, nations like the U.S., China, and NATO member-states are still investing in warships, suggesting that the world’s top war planners continue to believe in the viability of the warship.

But recent events have raised questions about survivability at sea. And as the history of warfare indicates, no system is untouchable, suggesting that even the mighty warship may one day become fully obsolete.”

Fortunately…..

I don’t have to worry about these issues and as we sailed into Halifax, I was focused on hitting a great brewery that was only three blocks from our pier and I’ll tell you about in the next post.

Cheers

External Photo Attribution

#1. Wikimedia Commons (File:2022-08-15 02 Wikivoyage banner image of Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.jpg – Wikimedia Commons). Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. Author: Gordon Leggett -15 August 2022.

#2. Wikimedia Commons (File:2024-06-10 01 MS VOLENDAM – IMO 9156515 – Halifax NS CAN.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. Author: Gordon Leggett – 10 June 2024.

#3. Schwabe Williamson & Wyatt website (https://www.schwabe.com/professional/david-bartz-jr/).

4. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons (File:Aerial view of the wreckage of the Francis Scott Key Bridge, in Baltimore – 240329-G-G0211-1001.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) As a work of the U.S. federal government, the image or file is in the public domain. Author: Petty Officer 1st Class Brandon Giles – 29 March 2024.

#5. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons (File:USS John R. Craig (DD-885) underway off Hawaii in 1967.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) As a work of the U.S. federal government, it is in the public domain in the United States. Author: PH2 Butler, USN – January 1967.

#6. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons (File:USS Bradley (FF-1041) underway at sea near San Clemente Island on 8 July 1976.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) As a work of the U.S. federal government, it is in the public domain in the United States. Author: PH3 Burgess, USN — 8 July 1976.

#7. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons (Ever Given in Suez Canal viewed from ISS (cropped) 3 to 2 – 2021 Suez Canal obstruction – Wikipedia) By NASA JSC ISS image library – https://eol.jsc.nasa.gov/SearchPhotos/photo.pl?mission=ISS064&roll=E&frame=48480, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=129747075- 27 March 2021.

#8. Wikimedia Commons (IMO 9811000 EVER GIVEN (09) – Ever Given – Wikipedia) By © S.J. de Waard / CC-BY-SA-4.0 (via Wikimedia Commons), CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=107989305 – 29 July 2021.

#9. Boxhub.com (file:///C:/Users/DWill/OneDrive/Documents/Pictures/2024%20Vacations/Cruise/Cruise%202/Halifax/assets_779e69b8bed04a8b81c09417c4f456d8_d8c122c0258847b3b15e3e1a215a403f.webp).

#10. Wikimedia Commons (Container 【 22G1 】 WTPU 010097(1)—No,1 【 Pictures taken in Japan – Twenty-foot equivalent unit – Wikipedia) By Gazouya-japan, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=38052679. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. 10 November 2012.

#11. Wikimedia Commons (File:Cargo Ship Puerto Cortes.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. Author:

Luis Alfredo Romero – 7 January 2023.

#12. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons (File:The battleship Arizona makes its way through the heaving seas of the Pacific. This photo was taken as the battleship steamed (79c61ee6-1dd8-b71b-0be4-1d4c5b920a28).jpg – Wikimedia Commons) This image or media file contains material based on a work of a National Park Service employee…..As a work of the U.S. federal government, such work is in the public domain in the United States. Author: NPGallery 20 June 2006..

#13. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons (File:USS Enterprise (CV-6) underway c1939.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) As a work of the U.S. federal government, it is in the public domain in the United States. Author: CDR William H. Balden, USNR-circa 1938-9.

#14. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons (File:USS North Carolina cropped Navy – Ships – Cruisers (165-WW-335D-4) – DPLA – bc4a2bb98571ecc905ebc7fc0aa53caa.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) This media file is in the public domain in the United States. Creator: War Department – 12 October 1912.

#15. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons (USS Wallace L. Lind (DD-703) underway in April 1970 (NH 107164) – USS Wallace L. Lind – Wikipedia) By PH1 D.M. Dreher, U.S. Navy – U.S. Navy photo NH 107164, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=42294064. 27 April 1970.

#16. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons (File:US Navy 050719-N-5526M-019 The guided missile cruiser USS Philippine Sea (CG 58 conducts Surface Action Group operations during exercise Nautical Union.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) Author: U.S. Navy photo by Photographer’s Mate 1st class Robert R. McRill – 19 July 2005.

#17. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons (File:USS Zumwalt (DDG-1000) departs Bath (Maine) on 7 September 2016.JPG – Wikimedia Commons) As a work of the U.S. federal government, it is in the public domain in the United States. Author: US Navy – 7 September 2016.

#18. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons (File:USS Gerald R. Ford (CVN-78) underway in the Atlantic Ocean on 9 October 2022 (221009-N-TL968-1248).JPG – Wikimedia Commons) As a work of the U.S. federal government, it is in the public domain in the United States. Author: U.S. Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jackson Adkins – 9 October 2022.

#19. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons USS Tulsa (LCS-16) in acceptance trials – List of current ships of the United States Navy – Wikipedia As a work of the U.S. federal government, it is in the public domain in the United States. Author: U.S. Navy/Austal USA 8 March 2018.

#20. Public Domain – Wikimedia Commons (File:Long Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM) launches from an Air Force B-1B Lancer.jpg – Wikimedia Commons) As a work of the U.S. federal government, it is in the public domain in the United States.Author: DARPA photo 5 September 2013.

#21. Wikimedia Commons (File:Iranian drone exercise in 2022 – Day 2 (52).jpg – Wikimedia Commons) Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. Author: Tasnim News Agency – 24 August 2022.